The Importance of Guidewire Bending: The Shape That Takes You Everywhere

Guidewire bending is not about aesthetics—it’s about intention. The shape you give to the wire defines whether you slide, drill, or anchor, and can even decide the outcome of an EVAR. In this article, we explore the essential curves and what they really mean inside the vessel.

A guidewire is never just a straight piece of metal.

That small bend you put at the tip — or even along the shaft — can turn a wire into an extension of your mind. Far from being aesthetic, bending is the grammar of the dialogue between operator and vessel. It decides whether the wire glides into a micro-channel, seeks a softer plane, or keeps bouncing back in frustration.

1) Sliding and Drilling

When we talk about wire techniques, most of the time it all comes down to two fundamental maneuvers: sliding and drilling.

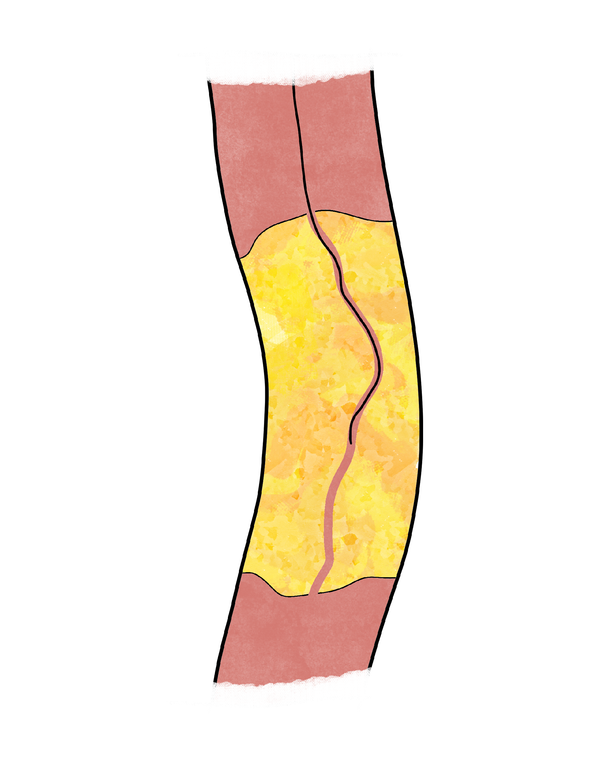

- Sliding is the art of delicacy. The wire is advanced with minimal pressure, coupled with a slow and gentle rotation. The aim is to let the tip find its way through CTOs, engaging tiny intralesional microchannels, remaining endoluminal and being as atraumatic as possible.

- Drilling is the opposite rhythm. Here the wire is rotated quickly, clockwise and counterclockwise, while applying a firm, controlled forward push. The goal is to progressively penetrate the cap and the CTO, advancing through areas of lesser resistance where sliding is no longer effective.

Both are simple in definition, but the difference is profound: sliding respects what exists, drilling creates what does not.

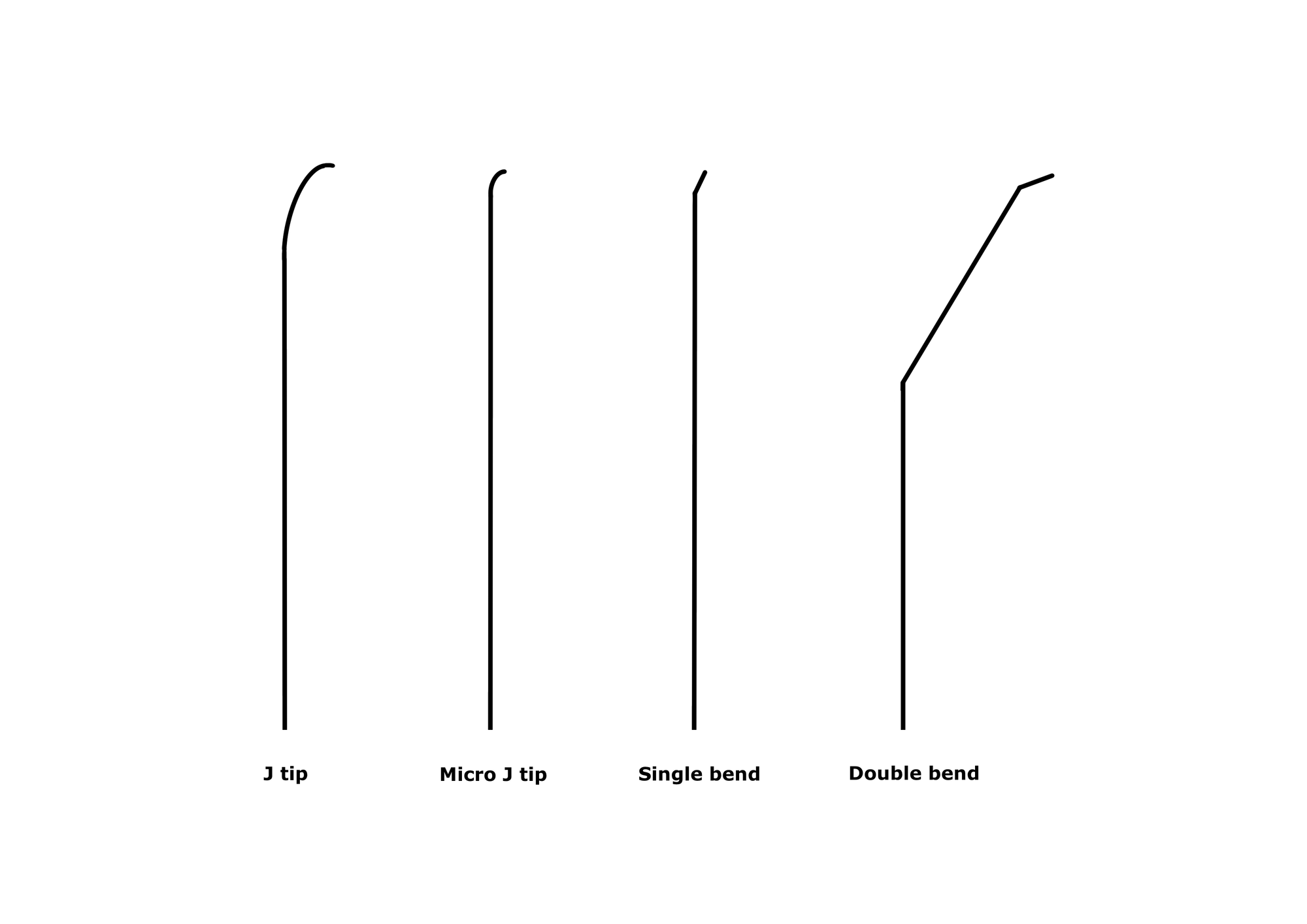

2) The base shapes: your universal language at the tip

- J-tip — it is your atraumatic, workhorse shape. Safe, stable, broadly applicable. Often the right default when you need to explore without harm.

- Single bend — the technical curve for targeted work, especially during handling as drilling. It lets you point, test, and commit. Bend the last 3 – 5 mm to an angle of 20 – 45°, depending on the need.

- Micro J-tip — a subtle J on the first 1–2 mm of the tip. This “in-between” shape excels during sliding, when you need to follow tiny channels inside the lesion: selective enough to stay on track, gentle enough not to jump out. Re-create the curve after a few passages if the tip straightens. Always avoid sharp angles: keep the curve soft and regular.

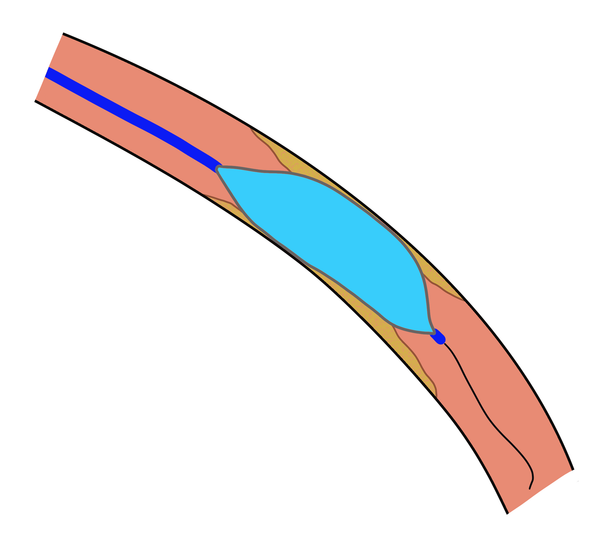

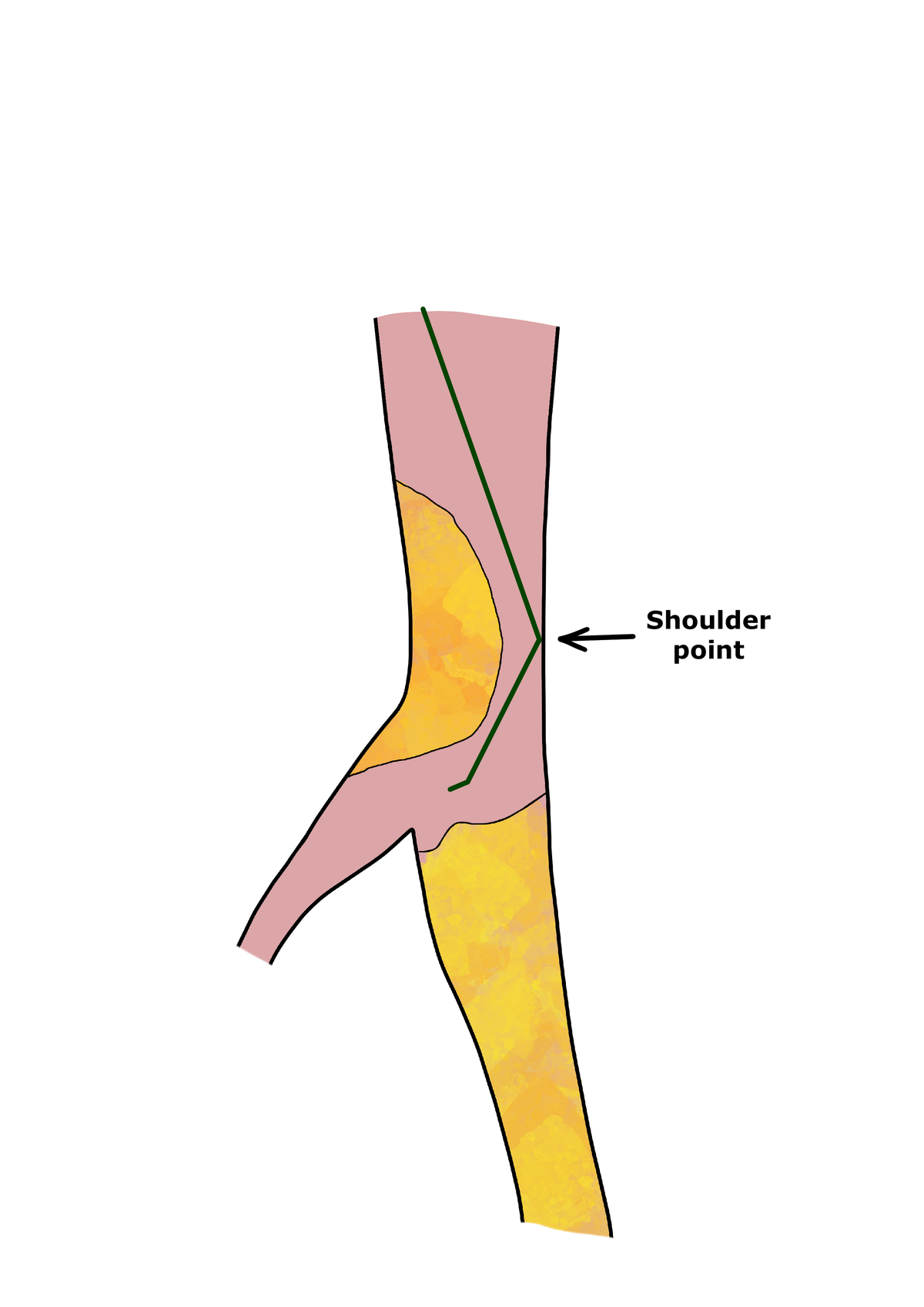

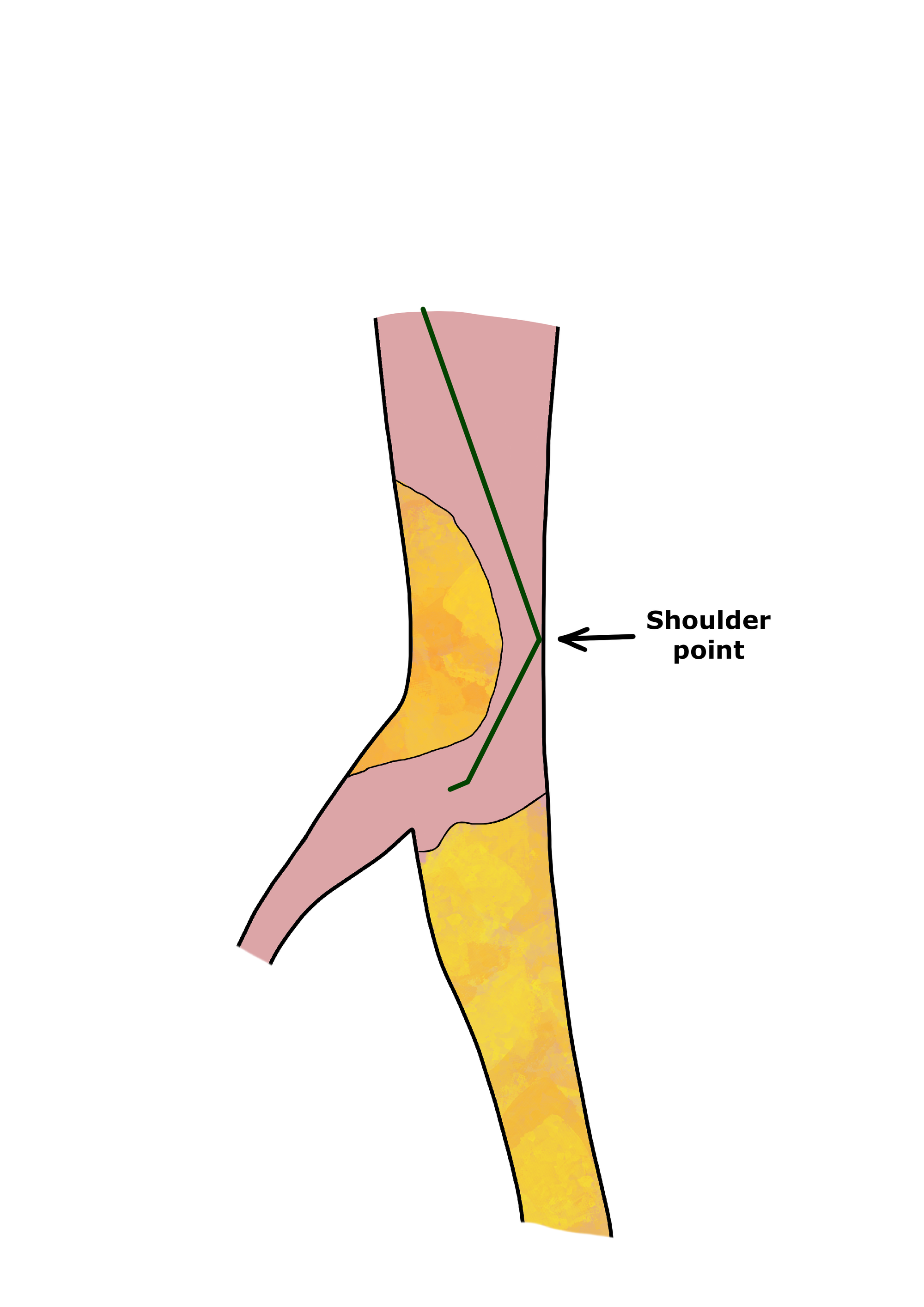

- Double bend — the specialist key for selective engaging. When you must enter a vessel at an awkward angle, the double curve gives you access and control – acting as a shoulder against the arterial wall.

3) Shape as an extension of technique

Bending is never aesthetic; it is pure functionality. That tiny curve is the translation of your intention into geometry — and geometry is how a vessel understands what you are asking.

Every maneuver with a guidewire is, in essence, a dialogue: the operator speaks through torque and pressure, and the artery responds with resistance, compliance, or a hidden track. The tip shape is the grammar of that language.

- With the right curve, a wire will not bounce off the plaque cap but will settle into a micro-channel, letting you glide forward instead of being constantly rejected.

- With the right curve, the wire can sense softer planes and direct itself toward the path of least resistance, making controlled penetration possible where brute force would only cause damage.

- With the wrong curve, even the most skilled hands end up in a frustrating loop: push, recoil, prolapse. The vessel simply “doesn’t hear” what you are trying to say.

This is why experienced operators rarely advance a completely straight wire into a complex lesion. A straight wire transmits force, but a shaped wire transmits intention. It can negotiate and cooperate with the vessel rather than fight it.

Mastering the bend is not about knowing every possible curve, but about recognizing how each shape makes the vessel listen differently.

4) Beyond occlusion: bending along the shaft (and why aneurysms care)

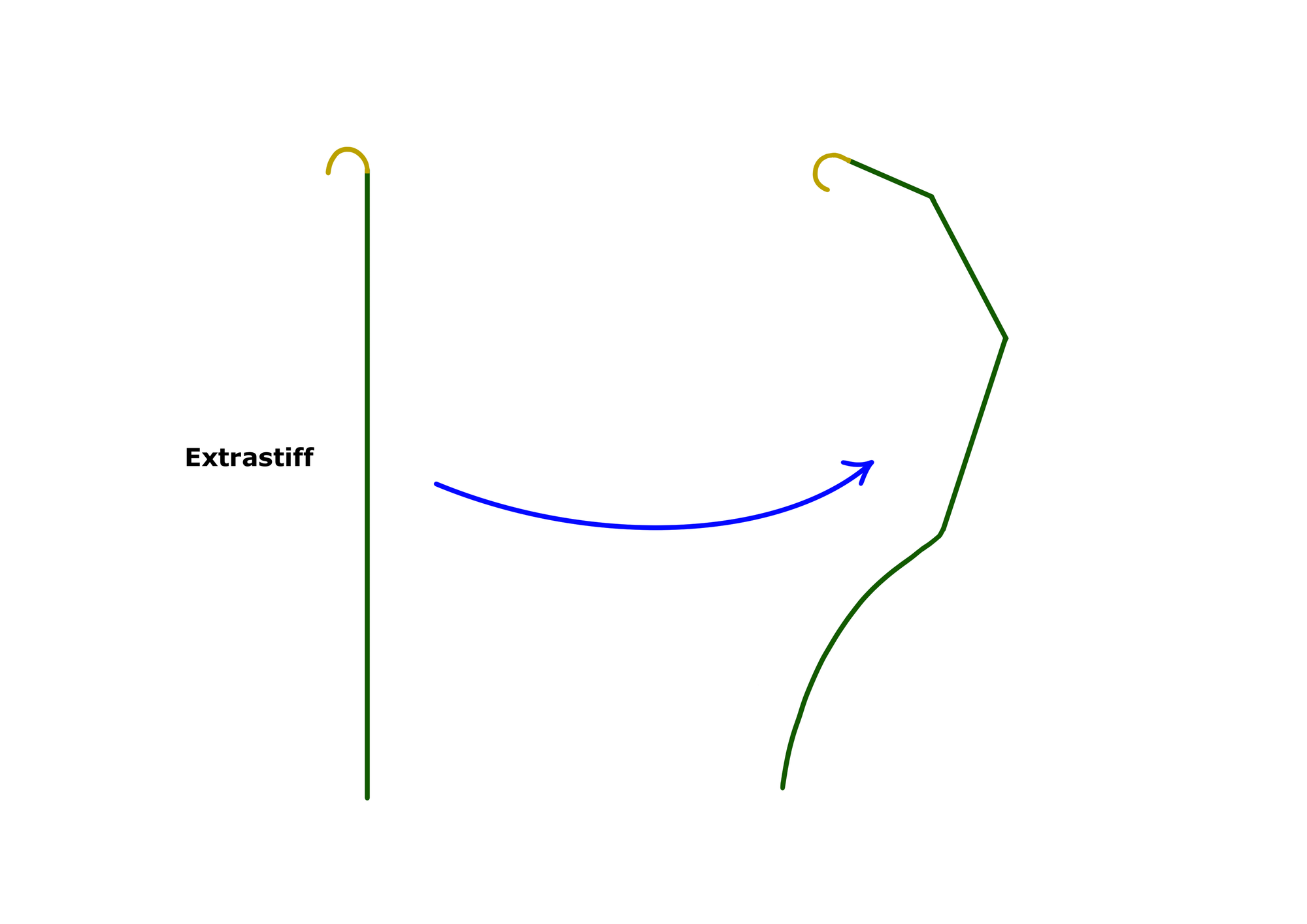

Bends don’t live only at the tip. Curvature along the GW shaft can be decisive — especially in aneurysmal work.

A completely straight extra-stiff wire tends to rectilinearize the aorta. This geometric distortion can alter the delivery path and compromise graft release, with the risk of malapposition, unintended coverage, or endoleak.

In tortuous anatomy, adding controlled bends to the GW shaft preserves the native aortic shape and true centerline, so devices track and deploy anatomically, not against the vessel.

Insider Tip. Shape the shaft to respect curvature where you deploy — the wire should follow anatomy, not redraw it.

Common Pitfall. A bend placed too proximally can migrate under respiratory/cardiac motion; place bends where they function (not just where they look good on the table).

5) Bend the wire, expand the map

The point is not to memorize every possible curve. The point is to recognize geometry and think different.

Bending is a technical gesture — and a mental one.It’s how you align intention with anatomy and let the vessel show you the path.

Those who stay inside the expected see a wire that bends. Those who think different open unexpected options— and find routes others don’t see.

Giovanni Solimeno

Founder of VasculHub